Primed for Action-HTA's Rory, Elisabetta and Vicky write for Building Magazine

Introduction and summary

The Consultation on the Future Homes Standard and the 2020 changes to parts L and F are, confusingly, contained in the same document. The proposals do not include the actual Future Homes Standard which is intended to be implemented in 2025 but instead suggests several parts of it which presage the changes proposed for 2025.

The changes proposed for 2020 include a major uplift in performance with the preferred option of a targeted 31% reduction in CO2 emissions compared to the previous, the biggest ever proposed improvement.

There is an alternative option of a 20% CO2 reduction which is not preferred but which is based on the proposed 2025 Future Homes Standard fabric performance level.

Whichever option is chosen, it is good to see a roadmap that the industry can examine and respond to which we haven’t had for many years as successive Governments have concentrated on delivering numbers of homes and have ignored or reduced environmental regulation.

In summary, the way to meet the standards is to adopt Air Source Heat Pumps or other similar technology based on electricity and move away from fossil fuels. When current designs are tested using the new values, they don’t meet the standard until gas is taken out of the energy mix. Why is this? Its because the carbon factor, a value representing the amount of CO2 produced by using different fuels, has dropped for electricity due to the renewable energy in the Grid, but not changed much for gas.

New projects in the GLA jurisdiction are already using the new CO2 factors and are omitting CHP and gas boilers in the main, and this consultation reflects that the rest of England and Wales will be catching up.

A fundamental change that this brings to design is that it is getting easier to achieve low-carbon design, provided that electricity is providing the energy. This could have unintended consequences, as developers will quickly respond to the changes and adopt the new technologies without much consideration of the consequences for the customer or for the designer. Air-Source Heat Pumps require an external fan unit to function and this has to be positioned outside the home, usually in a rear garden for houses and on the roof of apartments. Ensuring that these can be sited appropriately to avoid noise nuisance and a poor visual appearance is important. If anyone wants to know what happens when you retrofit them to a building, just visit any Asian city!

The Future Homes Standard

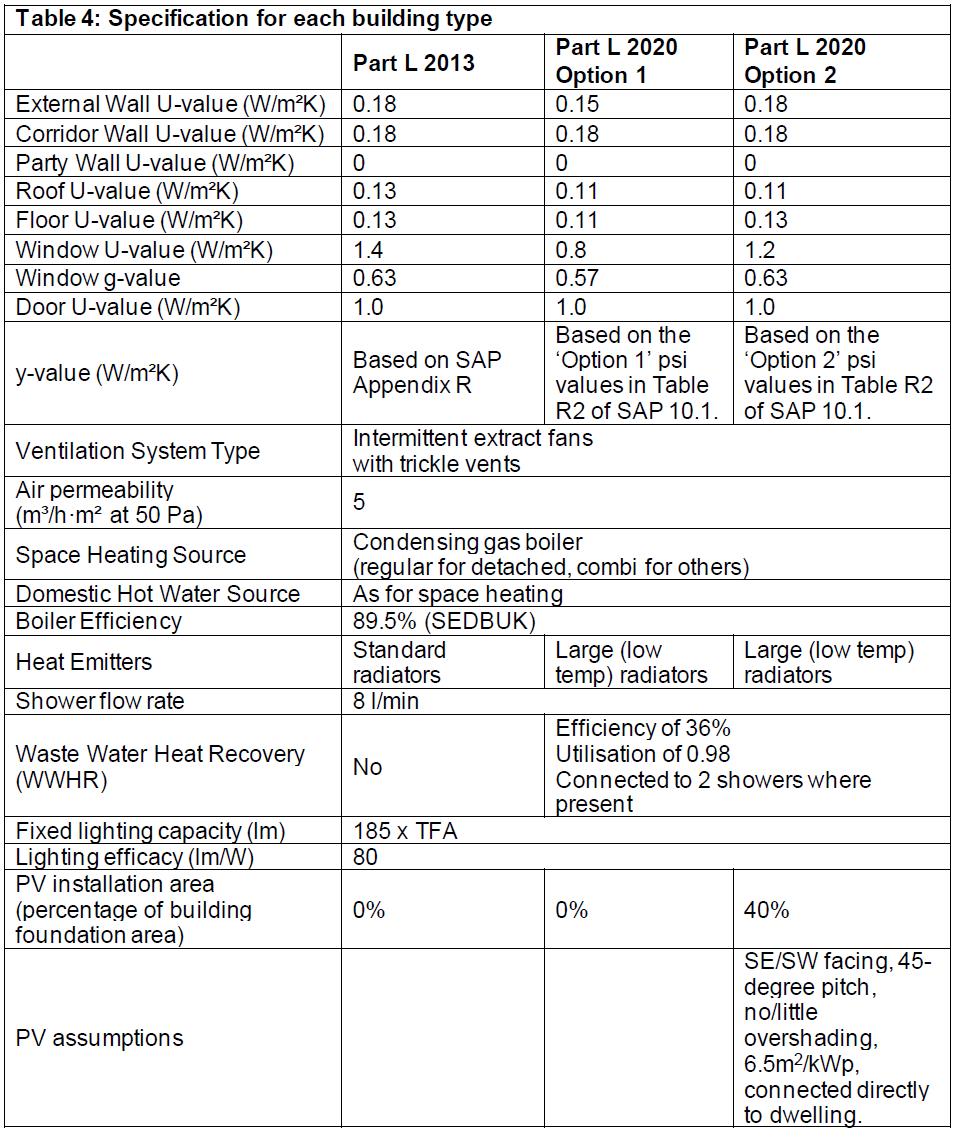

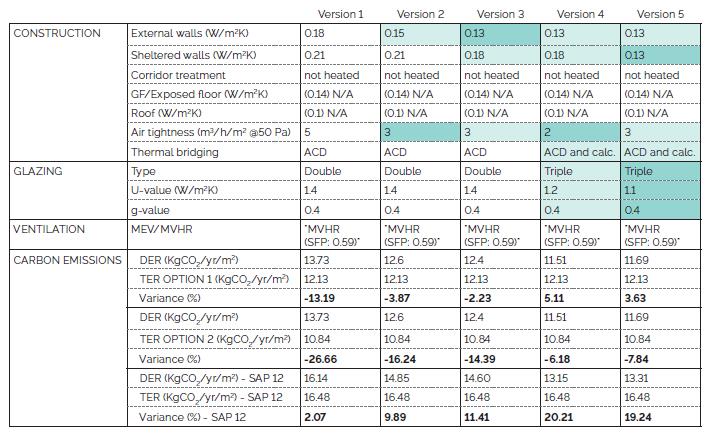

The Future Homes baseline fabric levels are suggested to be based on very low building fabric performance shown in the table below from the Impact Assessment document and identified in their table 4 as Part L 2020 Option 1. Option 2 in their table is the preferred 2020 proposed baseline fabric performance, this is the fabric performance against which improvements are measured.

Figure 1: Table 4 from the Consultation Impact Assessment.

The difference between Option 1 (which they propose to be implemented in 2025 as part of the Future Homes Standard) and Option 2, intended to be implemented in 2020 is as follows

- a relaxation in external wall U-values from 0.15 to 0.18,

- a relaxation in floor U-value from 0.11 to 0.13,

- a relaxation from 0.8 to 1.2 for window U-values (from triple to double-glazing)

- a different set of thermal bridging values,

- and the addition of PV panels for 40% of a low-rise house roof area.

The cumulative impact of these differences is to deliver a further 11% of CO2 emission reductions to the average baseline for dwellings, or the difference between Option 1 (20% reduction) and Option 2 (31%).

The majority of this is achieved by adding the PV panels in Option 2, as everything else is a reduction and this illustrates that we are now at the point where adding renewable energy systems to dwellings is a cheaper way of achieving CO2 emission reductions than adding building fabric improvements.

This demonstrates the significant changes that have happened in the PV market over the last decade where costs have reduced by approximately 90%.

What is less satisfactory about this approach of incremental improvements is that taking a cost-based view may prevent the right option from being chosen. MHCLG could take a more strategic view knowing that when regulatory changes are introduced across the UK the costs of implementation come down very quickly. This has been demonstrated by the quickly reduced implementation costs of the Code for Sustainable Homes. It seems to us that the preferred option should be the higher fabric performance from Option 1 as this sets a more demanding benchmark across the UK and costs will rapidly drop. Other improvements such as PV panels can be added as required to achieve the CO2 emission reductions, in the knowledge that the fabric performance has been pushed as far as is technically reasonable.

The Impact assessment measures the difference between the two options as 7.264bn Net present value and states that ‘the costs would fall with moderate efficiency gains through learning over time’ whereas my assessment is that the costs will rapidly fall because of the widespread adoption of the new methodology. The supply chain for housing in the UK is very good at innovating to meet new demands, and it is better for factory production to invest and make a single change rather than having to re-tool frequently.

An alternative approach could be

- A wall U-value of 0.15

- A floor U-value of 0.11

- A window U-value of 1.2

- An improved set of thermal bridging values

- A smaller amount of PV panels

The longer-term objective of the 2025 Standard is to introduce Heat Pumps as the preferred heating method. These rely on highly insulated dwellings to perform, as they are a slow response method of heating. They cannot deal with sudden changes in temperature as a gas boiler can, but they do reduce the reliance on fossil fuel combustion. More importantly they deliver highly efficient and cheap energy as they typically deliver about three units of heat for every one unit of electricity expended. This means that electrical heating is going to be cost-comparable with gas and will not increase customers’ bills.

The main thrust of the changes is that using electricity through Heat Pumps will meet the new targets, but properties with fossil fuels will find it increasingly difficult.

Pertinent Issues that are not addressed.

There are a number of issues that are not addressed in the consultation and do not appear to form part of MHCLG’s thinking. These range from the strategic to the relatively specific.

• Insulation values for corridor walls. Current practice assumes a lower performance for corridor walls to apartments when corridors are unheated. Experience over many years shows that corridors are much more likely to be a source of warmth as M+E services in ceilings tend to lose heat to corridors.

• Daylight. Improvements in fabric generally point towards lower sized windows as it is usually cheaper to make the windows smaller than to provide higher-performing windows. This has a knock-on effect on the size of windows. Without some basic requirements on adequate daylight levels in homes, there is a risk that some housebuilders will choose the lower quality option.

• Triple-glazing. While the energy saving benefits of triple-glazing is welcome, the embodied energy that goes into making the glass is not welcome. The impact assessment and consultation make no mention of embodied energy at a time when it is fast becoming the elephant in the room.

• Post-Occupancy Evaluation. The addition of site photographs of construction activities is welcome as it will help to provide some much-needed oversight of site operations. But that falls a long way short of actual post occupancy testing. It is important that there is routine feedback to the industry on actual performance so that we do not continue to build homes thinking that we have solved the problem, when actually we are simply leaving a problem for someone else to fix at a later date.

• Cooling. There is little doubt that the use of heat pumps which can be switched to a reverse cycle and used to cool apartments is likely to become widespread. Overheating in apartments is already common before these standards are implemented but there is little mention of either in the document, it needs to move much further up the agenda.

• Modelling: It is unlikely that SAP in its current form can continue to be the tool that is used to model housing performance. It is a crude tool for a complex situation. In addition to the issues above, there is the discrepancy between the behaviour of apartment buildings and houses. Taller apartment buildings are a very different set of problems to analyse than low rise housing and it is probable that a better calculation methodology such as dynamic simulation would give more accurate and more useful results.

• Plug Loads: The impact of plug loads on energy footprint is rising, as a proportion of energy use, and this is heavily dependant on occupancy levels and behaviour. But it still needs to be considered as we cannot achieve a fully zero carbon home without it, so our energy production from new homes needs to grow to offset this additional demand.

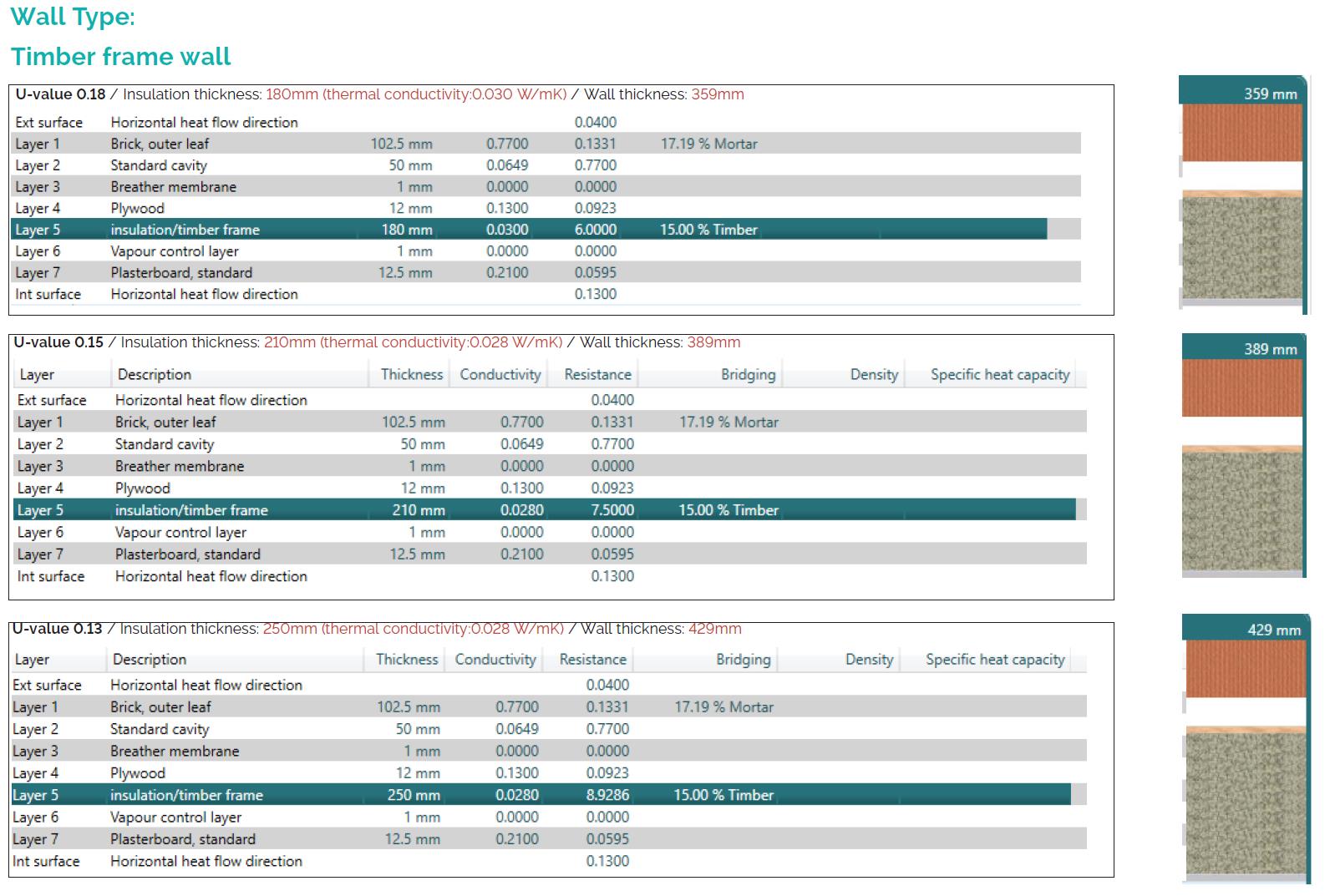

Wall Thickness

The impact of the Grenfell fire continues to reverberate through the construction sector and one of the many impacts is the insistence of clients on non-combustible insulants irrespective of the regulatory position. The impact of this is that lower performing insulants are being used which in turn is increasing wall thicknesses. The industry needs an affordable non-combustible high-performing insulant as soon as possible to address this issue.

Figure 2: U-Values and Wall Thickness.

All-Electric

Taking an all-electric approach also means that as the Grid is decarbonised, homes based on electricity become lower and lower emitters of CO2. By connecting them to the Grid they are effectively being future-proofed, providing that we continue to invest in wind and renewable production of electricity. Note that there is no mention of shale gas anywhere in the consultation! The rapidly reducing costs of offshore wind have demonstrated here and elsewhere that a low carbon future is possible and, in our grasp, a fact to be celebrated but also acted upon!

Developers will be attracted by the possibility of using direct electric heating in buildings which would simplify services design and lower costs significantly, but unless the homes are super-insulated the costs to end users will be punitive. Compared to an Air-Source Heat Pump they will cost customers three times as much to run. It is good that there is a provision in the consultation for a specific report for homeowners covering this issue, introducing a report on running costs for customers.

Competing Standards

This focus on low energy dwellings does also beg the question about alternative approaches such as Home Quality Mark, PassivHaus or ActiveHouse which rely on very high fabric efficiency. Should they be allowed as alternative approaches? Is it not time to acknowledge that there are multiple ways of answering the low-energy/low-carbon question in housing?

Local Government Standards

There is one worrying line in the consultation that seeks agreement to the notion that Local Government should no longer be able to set higher standards than those in the Building Regulations. It could be argued that this is a quid pro quo to housebuilders for setting them more demanding targets, reducing the need for them to apply different ones in different jurisdictions. We do not support this approach for a number of reasons.

It has never made sense for England and Wales to use the same domestic energy standard for Cornwall, London, Bangor and Newcastle. There are many differences in annual sunshine, rainfall and exposure conditions and suggesting that the same dwelling could be used in all three is not sensible and flies in the face of other Government guidance which seeks to enhance local diversity in design. It makes little sense to offer design diversity with one hand and then to take it away with the other.

In addition, housebuilders are local businesses with national management. Those local businesses are highly skilled in dealing with those local conditions and recognise that to get local planning permissions they must take account of local design requirements, including energy targets.

Furthermore, this Government and previous Governments have been very unpredictable vis-a-vis environmental regulation, and to suggest that there is now a firm Government commitment to a particular direction and a commitment to maintain it for the foreseeable future is unconvincing. Who is to say that a future version of a Brexit-Tory coalition would not reverse these proposals? Fortunately, local authorities and the mayoralties, particularly the GLA, have held the ring on stretching environmental targets for some time now, and these proposed changes to Part L are catching up to where the GLA already are to some degree, but without the demanding fabric targets enshrined in the London Plan.

The higher sales values in the South-East enables that region to pioneer more stretching targets and absorb those costs easily, where other regions struggle with viability going beyond Building Regulations. An approach that allows for higher targets in areas with higher values is sensible as it means that we can use those areas to pioneer new approaches and bring down the costs to enable adoption in other regions. In the long term this is likely to encourage a move towards a lower carbon future more quickly than by applying a one-size-fits-all approach across England and Wales.

Part L Standards for New Homes in 2020

We have carried out some preliminary testing using the test version of SAP 10.1 provided by BRE. This is a preliminary version and results will be different in the final version, but nontheless the results are instructive in showing the direction of travel, particularly when analysis of the same unit types is compared with SAP 2012

The four versions for HVAC systems we chose are:

HVAC 1: a gas boiler

HVAC 2: ASHP with 1kwp PV panels

HVAC 3: ASHP and WWHR with 1 Kwp PV panels

HVAC 4: ASHP and WWHR with 3Kwp PV panels and solar thermal.

ASHP = Air-Source Heat Pump

WWHR = Wastewater Heat Recovery

Kwp=Kilowatt peak production

PV = photovoltaic panels

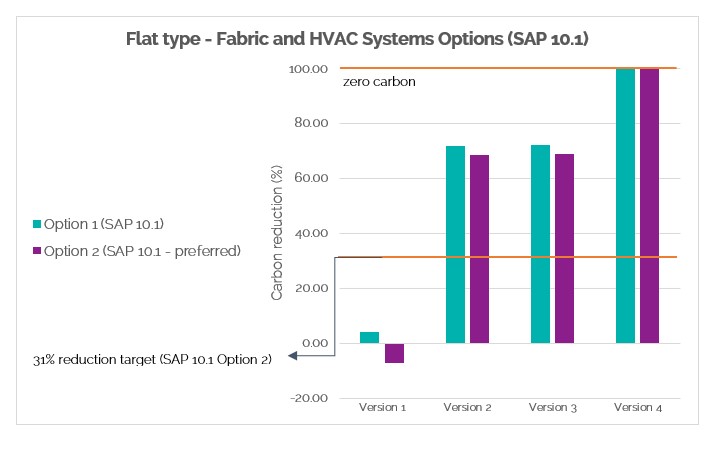

Figure 1. Testing Apartments against the options.

The testing we have done with the 2020 proposed standards reveals some important issues particularly relating to the impact of adding ASHP’s instead of gas boilers and the need for a higher baseline fabric target.

Figure 1 shows testing of a typical apartment type against the two options for the new standard.

What it shows is that when apartments are heated with gas in HVAC 1 they fail in both options, but when the heating is changed to an Air-Source Heat Pump they pass, and when PV systems are added both options become nearly zero carbon. Note that there is not much difference in performance between the two options.

Figure 2 Testing Apartments against different fabric options.

The five versions are as follows:

This test illustrates the performance changes when compared to the current standard in grey. It shows that in most cases apartments heated using gas boilers will not pass with fabric only improvements, no matter how high the fabric performance is. The most extreme options include 0.13 walls, an airtightness of 3 and Mechanical Ventilation with Heat Recovery, this doesn’t even meet the 20% improvement in Option 1, where the same improvements in the current version of SAP does meet a 20% improvement.

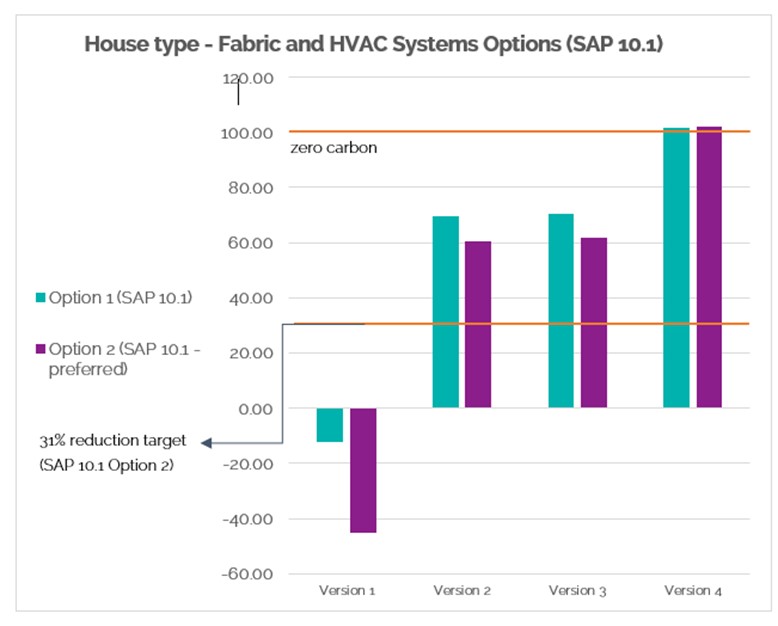

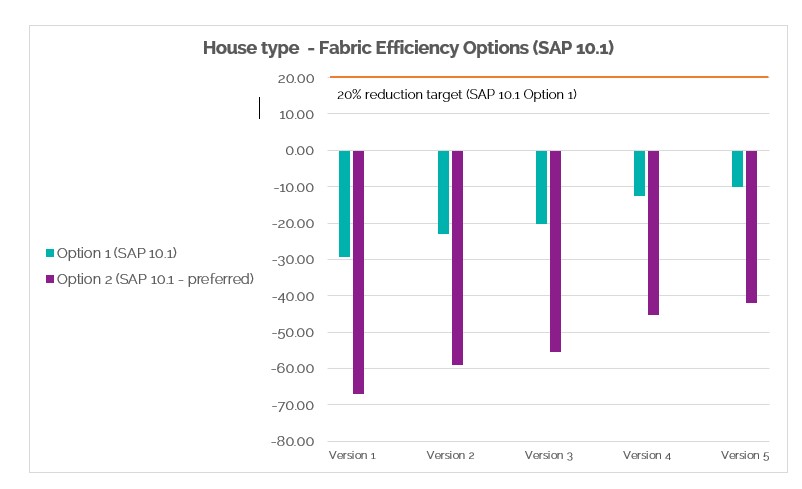

Figure 3: Housetype fabric options.

This demonstrates that even with very high fabric performance a house heated by gas doesn’t meet the standard.

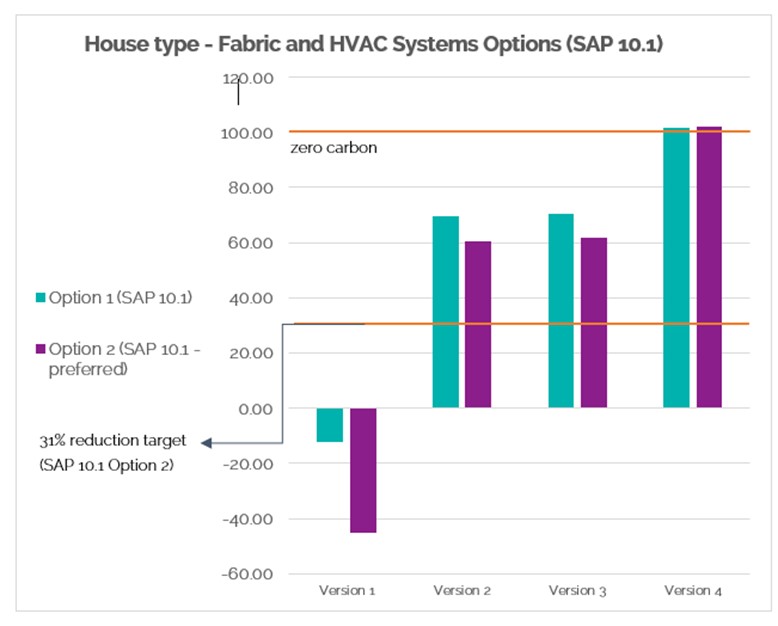

Figure 4 Testing House environmental systems.

Figure 4 shows that with a good level of fabric, it still is necessary to add Air-Source Heat Pumps to the dwelling and move away from gas to meet a 20% improvement.

The four versions of services are the same as for the apartment types.

All of this reveals the necessity of setting a strong baseline fabric performance, as without it, there is a temptation for developers to adopt Heat Pumps and not improve the fabric performance at all.

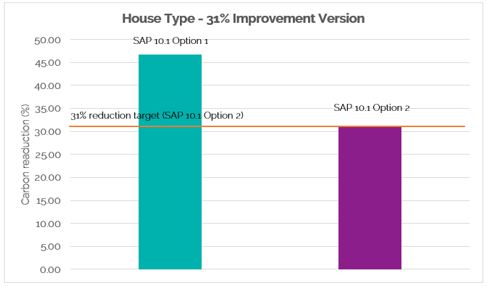

Figure 5 Meeting the baseline performance.

Figure 5 illustrates what happens when a design is tailored to meet the 31% target specifically. Reducing fabric performance to low levels and adding an ASHP allows a dwelling to meet Option 2 exactly, and the same building tested against Option 1 achieves a 46% improvement. Because adopting ASHP boosts performance so much, the only way to hit the target is to drop fabric performance. The U-value of the walls in this option is U=0.28 and the windows are U=1.6 with natural ventilation! This illustrates the neccessity of having a strong fabric baseline, as without it the temptation will be to reduce fabric performance and increase customers energy bills.

Compliance performance and Providing Information

The consultation includes measures forcing construction teams to supply photographic evidence of the construction of all major junctions to enable the SAP Assessor to sign off the performance of the building and issue the EPC. The current requirement is a signature from the contractor saying that the design requirements have been met. Given the evidence that actual performance is generally lower than design performance this signals an important first step in improving site construction quality. At HTA we would say that the best way to ensure this is to move the construction offsite but that is for a different article.

Generally we support the ambition to have better clarity on what was actually constructed so that the end customer can be more confident that what they have bought or rented is actually what they paid for and expected.

Transitional Arrangements

The consultation aims to change the transitional arrangements to be more in favour of the customer. The proposal is to end the current extraordinary loophole where housebuilders can start work on a large site which could take a decade to build out and to fix the building control requirements for the entire site at the beginning. The proposal is changing to be at a building scale and not a site scale, which is a major change and will, if implemented, have a huge impact on housebuilding practice.

Current practice means that swathes of new homes being constructed and sold on large sites across the UK are being built to a previous version of the Building Regulations for many years after those regulations have been superseded. In all other industries the provider of a product is required to sell the product at current levels of regulatory compliance. In housing there is currently nothing to tell the customer that the home does not meet current regulatory compliance.

Conclusions

This consultation signals a major change in energy policy in the UK, the penny has dropped that we can decarbonise the electricity grid much faster than the gas grid, and policy will naturally take the easier and cheaper route to a low-carbon economy.

The move to Heat Pumps is a strategic one, and an obvious one, but the supply chain for it in the UK is small and will need to rapidly scale up to meet demand and to supply repair and maintenance services.

This will open up a big gap in practice between new build and existing properties. Existing properties cannot often use Heat Pumps as they are simply too inefficient. The next obvious decarbonisation policy is a holistic energy efficiency drive in the existing stock, and/or a programme of demolition and replacement of the worst performing stock.

The mood music between Govt and housebuilders appears to have changed a lot, and it will be interesting to see what happens next in that relationship. Has the enormous profits in the housebuilding sector, which would usually be a cause for celebration in a Conservative Govt, changed the Govts mind about where policy should be going next?